The Jack Birch Unit

In May 1992, we saw a significant step forward with the opening of the Jack Birch Unit, based at the University. Over the years, York Against Cancer has supported a number of research projects and PhD studentships at the Unit. It has also helped to purchase specialised research equipment, including an infra-red gel scanner and a first-in-the-world high-tech microscope, which means our scientists are able to work at the very forefront of research.

We continue to support the unit today as part of a five-year £1 million programme, funding a senior scientist (Dr Simon Baker), as well as secretarial and laboratory support and a portion of the Director’s salary. Other research that goes on in the Jack Birch Unit is funded by grants from government-funded research councils, other medical charities and industry.

Bladder cancer research

In the past, research at the Jack Birch Unit has included work on gastric, colon and gall bladder cancers. These days, research work at the unit is mainly focused on human bladder cancer, also known as urothelial cancer. Bladder cancer is thought to be a particular problem in parts of Yorkshire because of the county’s industrial heritage.

A generous legacy to York Against Cancer has meant that recently £100,000 has been given to the prostate cancer research team headed by Professor Norman Maitland, the University of York’s Chair of Molecular Biology, who has been investigating prostate cancer for many years. The bequest will help develop drug treatments that it is hoped will kill off rogue cancer stem cells that make prostate cancer a complex disease.

York Against Cancer has also funded research conducted by specialists at York Hospital, such as work by Dr James Turvill, a consultant gastroenterologist, into a possible test to identify people at risk from developing bowel cancer.

Unique approach

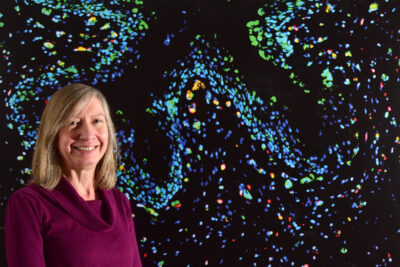

Cancer research at the Jack Birch Unit is based on a unique approach, as Director of the Unit, Professor Jenny Southgate explained. “Much cancer research starts with examining the tumours, whereas our research starts with normal human cells and tissues. It’s rather like studying a runaway car – how could you find out if the accelerator is stuck on or the brakes have failed if you did not know how a car works in the first place?”

The approach pioneered in the Jack Birch Unit means that they can help to understand how cancer genes are involved in the early development of cancer. “This is the first important step in finding new therapies to block cancer growth,” said Jenny.

Find out more about the Jack Birch Unit here.